Navigating Risks and Barriers for LGBTQ Employees: Perspectives from Managers, HR Professionals, Discrimination Experts, and LGBTQ Individuals – A synthesis of the project ”Minority stress at work”

Principal Investigator

Tove Lundberg, Associate Professor, Department of Psychology, Lund university, Lund Sweden (tove.lundberg@psy.lu.se)

Collaborators

Benjamin Claréus, PhD and Senior Lecturer, Department of Psychology, Kristianstad University, Kristianstad, Sweden

Amanda Klysing, PhD and postdoc, Department of Psychology, Lund University, Lund, Sweden

Anna Malmquist, Associate Professor, Department of Behavioral Sciences and Learning, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden

Theodor Mejías Nihlén, MSc and PhD candidate, Department of Behavioral Sciences and Learning, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden

Matilda Wurm, PhD and Senior Lecturer, School of Behavioral Social and Legal Sciences, Örebro University, Örebro, Sweden

Funding

Afa Insurance grant no. 200413

Background and aim

Many lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) people experience a positive and accepting — or at least neutral — work environment (MYNAK, 2022). However, compared to heterosexual cisgender individuals, LGBTQ individuals face higher levels of discrimination, microaggressions and incivility at work, which lead to negative health and work-related outcomes (Cancela et al., 2024; Lacatena et al., 2024; Maji et al., 2023).

According to Swedish law, employers are required to take active measures to promote equal opportunities and prevent discrimination. To understand how this can be achieved effectively, more research is needed. However, few studies in Sweden have explored the work experiences and needs of LGBTQ employees. Addressing this gap was the aim of the three-year research project Minority Stress at Work (funded by Afa Insurance).

Methods and Materials

Interview data. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 83 LGBTQ individuals about their work-life experiences (ages 17–74, mean = 35), and 26 professionals (managers, HR partners, discrimination experts) about their roles in preventing discrimination and promoting LGBTQ inclusion. Participants were recruited via social media, LGBTQ organizations, direct contact and snowball sampling.

Reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2021) and interpretative repertoires analysis (Wetherell & Potter, 1988) were used.

Survey data. A survey was completed by 2,153 participants (1,252 LGBTQ and 901 heterosexual cisgender individuals) through targeted sampling (1,257 participants via social media and RFSL; 231 joined a 1-year follow-up) and random sampling (896 participants from a population-representative sample; 108 joined the follow-up).

The survey measured:

- Workplace environment (e.g., demands, support, relationships, diversity, inclusion) on a 5-point Likert scale

- Job satisfaction on a 5-point Likert scale

- Workplace Incivility Scale (WIS; Schad et al., 2014)

- Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995)

- Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., 1985)

- Brief COPE (BCOPE; Carver, 1997)

- Coping With Harassment Scale (CWH; Cortina & Magley, 2009 – for those reporting mistreatment), and

- Open-ended questions were also included

ANOVAs, t-tests, regressions, non-parametric tests, mixed modeling, Latent Class Analysis, and Discriminant Tree Analysis were used.

Main results

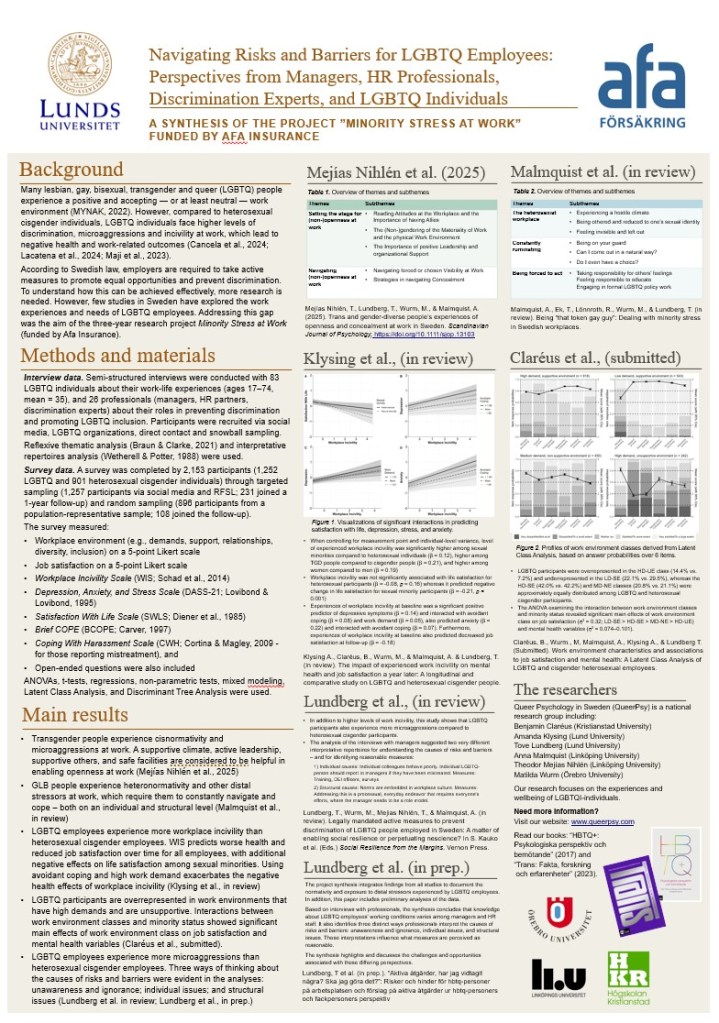

- Transgender people experience cisnormativity and microaggressions at work. A supportive climate, active leadership, supportive others, and safe facilities are considered to be helpful in enabling openness at work (Mejías Nihlén et al., 2025)

- GLB people experience heteronormativity and other distal stressors at work, which require them to constantly navigate and cope – both on an individual and structural level (Malmquist et al., in review)

- LGBTQ employees experience more workplace incivility than heterosexual cisgender employees. WIS predicts worse health and reduced job satisfaction over time for all employees, with additional negative effects on life satisfaction among sexual minorities. Using avoidant coping and high work demand exacerbates the negative health effects of workplace incivility (Klysing et al., in review)

- LGBTQ participants are overrepresented in work environments that have high demands and are unsupportive. Interactions between work environment classes and minority status showed significant main effects of work environment class on job satisfaction and mental health variables (Claréus et al., submitted).

- LGBTQ employees experience more microaggressions than heterosexual cisgender employees. Three ways of thinking about the causes of risks and barriers were evident in the analyses: unawareness and ignorance; individual issues; and structural issues (Lundberg et al. in review; Lundberg et al., in prep.)

Mejías Nihlén, T., Lundberg, T., Wurm, M., & Malmquist, A. (2025). Trans and gender-diverse people’s experiences of openness and concealment at work in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.13103

The workplace is an important part of many people’s lives. Many transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) individuals have negativeexperiences of their workplace due to discrimination and cisnormativity. Whether or not to be open about TGD experiences, andthe degree of openness, is something many TGD individuals struggle with at work. Openness is related to well-being and job satis-faction and is therefore important to consider when understanding TGD individuals’ work situations. This article examines TGDindividuals’ experiences of openness and concealment regarding their TGD experience at work. Thirty TGD adults from Sweden participated in online semi-structured interviews, which were analyzed using thematic analysis. Results show that the organizational climate and physical environment, as well as leadership and human resources, set the stage for an inclusive or excluding workplace for TGD individuals. For the individual, these aspects are taken into consideration when weighing up the risks and advantages of being open about their TGD experience at work. Factors such as work climate, the presence of LGBTQ+ colleagues,and access to safe facilities make a difference in the decision about, and experience of, being open or concealing one’s TGD experience at work. Personal values, and a prerequisite to pass or not, affect decisions concerning disclosure and create different challenges in managing working life as a TGD individual. Findings are helpful in better understanding TGD people’s situation at work and are of use for work management and policymakers in creating a better work environment for TGD individuals.

Malmquist, A., Ek, T., Lönnroth, R., Wurm, M., & Lundberg, T. (in review). Being “that token gay guy”: Dealing with minority stress in Swedish workplaces.

Employers in Sweden are mandated to take active measures to prevent discrimination against sexual minorities. While it is important that relevant measures are taken, knowledge is lacking about cisgender LGB people’s minority stress experiences at Swedish workplaces. The present work is based on a thematic analysis of interviews with 53 cisgender LGB participants, focusing on how they experienced and dealt with minority stress experiences at work. Results are drawing on the minority stress model (Meyer, 2003), showing distal minority stress, due to a heteronormative work climate. This led to proximal stressors, such as constantly being on your guard. Participants took considerable responsibility for others’ feelings, felt a responsibility to educate on LGBTQ issues, and sometimes engaged in formal policy work to improve workplace conditions. The study points at the importance of shifting the burden of workplace minority stress from individual LGB people to employers.

Claréus, B., Wurm., M, Malmquist, A., Klysing A., & Lundberg T. (Submitted). Work environment characteristics and associations to job satisfaction and mental health: A Latent Class Analysis of LGBTQ and cisgender heterosexual employees.

The purpose of the study is to understand the characteristics of work environments among LGBTQ and heterosexual cisgender employees. 2153 currently employed Swedish-speaking participants (Mage = 38.22; in total, 58.2% identified as LGBTQ) were recruited via purposive as well as probabilistic methods. Latent Class Analysis suggested four classes of work environments, namely high demand, supportive environment (HD-SE; 42.6%), low demand, supportive environment (LD-SE; 25.2%), medium demand, non-supportive environment (MD-NE; 20.9%), and high demand, unsupportive environment (HD-UE; 11.2%). The HD-UE was significantly overrepresented among LGBTQ participants, particularly among those who identified as trans- and gender diverse. Comparisons on job satisfaction and mental health variables suggest that work environment class (η2 = .07–.32, p < .001) was more important than minority status (η2 = .002–.018, p = .015–.418) in explaining interindividual differences, such that the MD-NE and HD-UE classes fared the worst. However, LGBTQ participants reported exposure to more incivil behaviors regardless of class assignment (η2 = 0.002, p = .011), and workplace incivility was strongly associated with job satisfaction as well as mental health (|ꞵ| = .13–.35, p < .001). The enactment of structural injustice and discrimination of LGBTQ people in the workplace and in general life is discussed.

Klysing A., Claréus, B., Wurm, M., & Malmquist, A. & Lundberg, T. (in review). The impact of experienced work incivility on mental health and job satisfaction a year later: A longitudinal and comparative study on LGBTQ and heterosexual cisgender people.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and queer (LGBTQ) employees report more negative workplace experiences than their heterosexual and cisgender counterparts. This includes higher exposure to subtle slights at work, such as workplace incivility, which may negatively impact health and work-related outcomes. However, resilience factors such as coping strategies, work support, and work demand can potentially moderate this impact. The current study employs a longitudinal design to examine if workplace incivility acts as minority stressor for LGBTQ people in Sweden.

Using a digital survey, (N = 1752; Mage = 38.95; 54,6% sexual minority and 17.14% with trans experience), we examined the relationship between workplace incivility and health outcomes (life satisfaction, depression, stress, anxiety) and job satisfaction a year later. We also explored if work support, demand and personal coping strategies moderate the impact of incivility. LGBTQ employees reported experiencing more workplace incivility than heterosexual cisgender employees. Workplace incivility predicted worse health and reduced job satisfaction over time for all employees, with additional negative effects on life satisfaction among sexual minorities. Use of avoidant coping and high work demand exacerbated negative health effects of workplace incivility. These results highlight the need to address low-intensity workplace mistreatment to promote inclusive and supportive work environments.

Lundberg, T., Wurm, M., Mejias Nihlén, T., & Malmquist, A. (in review). Legally mandated active measures to prevent discrimination of LGBTQ people employed in Sweden: A matter of enabling social resilience or perpetuating nescience? In S. Kauko et al. (Eds.) Social Resilience from the Margins. Vernon Press.

Swedish LGBTQ individuals report significantly higher rates of mental health challenges compared to heterosexual cisgender individuals—a disparity that motivates our research. Since 2017, we have applied the minority stress model to understand how both distal societal factors—such as discrimination, healthcare access, and violence—and proximal factors—like internalized stigma and identity concealment—contribute to this gap. We also draw on microaggression theory to examine the subtle, often unconscious discriminatory interactions that further marginalize LGBTQ individuals.

While psychology has traditionally emphasized individual resilience, Meyer (2015) warns that this focus may obscure the societal roots of minority stress. Instead, he advocates for an ecological view of resilience, aligning with social resilience research. In this chapter, we use findings from a 2023 survey of 509 participants and interviews with eight managers to explore how integrating LGBTQ psychology with social resilience frameworks can offer a more holistic approach to addressing mental health disparities.

We identify risks for discrimination and barriers to equal opportunities that LGBTQ employees face in the workplace. Additionally, we analyze two distinct interpretative repertoires used by managers in their reasoning about the active measures they are legally required to implement under Swedish law.

Lundberg, T et al. (in prep.). “Aktiva åtgärder, har jag vidtagit några? Ska jag göra det?”: Risker och hinder för hbtq-personer på arbetsplatsen och förslag på aktiva åtgärder ur hbtq-personers och fackpersoners perspektiv

This is a synthesis of the results from the research project “Minority Stress at Work”, which is based on the requirements of the Swedish Discrimination Act for employers to take active measures against discrimination. The results show that LGBTQ individuals are more exposed to negative treatment in the workplace than heterosexual cisgender individuals, and that this has adverse effects on health and job satisfaction. The findings also reveal that knowledge about the working conditions of LGBTQ people varies among managers and HR partners, which shapes how they perceive risks and obstacles in the workplace. This, in turn, frames their views on which measures are considered reasonable. Continued research and discussion are important for the Discrimination Act to achieve its intended impact.

References on poster

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Sage.

Cancela, D., Stutterheim, S. E., & Uitdewilligen, S. (2024). The Workplace Experiences of Transgender and Gender Diverse Employees: A Systematic Literature Review Using the Minority Stress Model. Journal of Homosexuality, 1-29.

Carver, C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol’too long: Consider the brief cope.International journal of behavioral medicine, 4(1), 92-100.

Cortina, L. M., & Magley, V. J. (2009). Patterns and profiles of response to incivility in the workplace.Journal of occupational health psychology, 14(3), 272.

Diener, E., et al. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of personality assessment, 49(1): p. 71-75

Lacatena, M., Ramaglia, F., Vallone, F., Zurlo, M. C., & Sommantico, M. (2024). Lesbian and Gay Population, Work Experience, and Well-Being: A Ten-Year Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(10), 1355.

Lovibond, P.F., & Lovibond, S.H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour research and therapy, 33(3): p. 335-343.

Maji, S., Yadav, N., & Gupta, P. (2024). LGBTQ+ in workplace: A systematic review and reconsideration. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 43(2), 313–360. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-02-2022-0049

MYNAK (2022). HBTQ-personers organisatoriska och sociala arbetsmiljö – en kunskapssammanställning. (Kunskapssammanställning 2022:7). https://mynak.se/publikationer/hbtq-personers-sociala-och-organisatoriska-arbetsmiljo/

Schad, E., Torkelson, E., Bäckström, M., & Karlson, B. (2014). Introducing a Swedish translation of the workplace incivility scale. Lund Psychological Reports, 14(1), 1-15.

Wetherell, M., & Potter, J. (1988). Discourse analysis and the identification of interpretative repertoires.Analysing everyday explanation: A casebook of methods, 1688183.